Assessing the impact of farm ponds on agricultural productivity in Northern India

Introduction

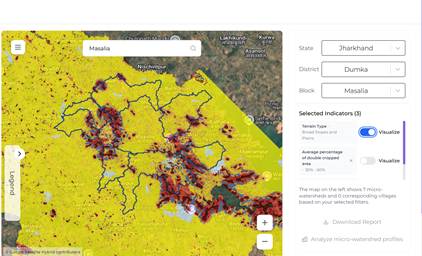

Government welfare schemes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in India fund the creation of assets for natural resource management in rural villages to support farmers for their agricultural and livelihoods-based needs. With most agriculture in India being rain-fed, structures such as farm ponds, check dams, trenches and bunds play a crucial role in supporting groundwater recharge and providing critical life saving irrigation to the crops in times of dry spells and droughts. In this study, we investigate the impact of farm ponds built under the MGNREGA scheme in Northern India as a source of protective irrigation for cropping areas in their immediate neighbourhood.

We assess the impact of farm ponds on the following aspects: (i) we study their impact on agricultural productivity for up to five years since their construction, (ii) we separately study their impact in drought years during this period, (iii) we study the extent to which they are able to to reduce the sensitivity to droughts of sites having farm ponds.

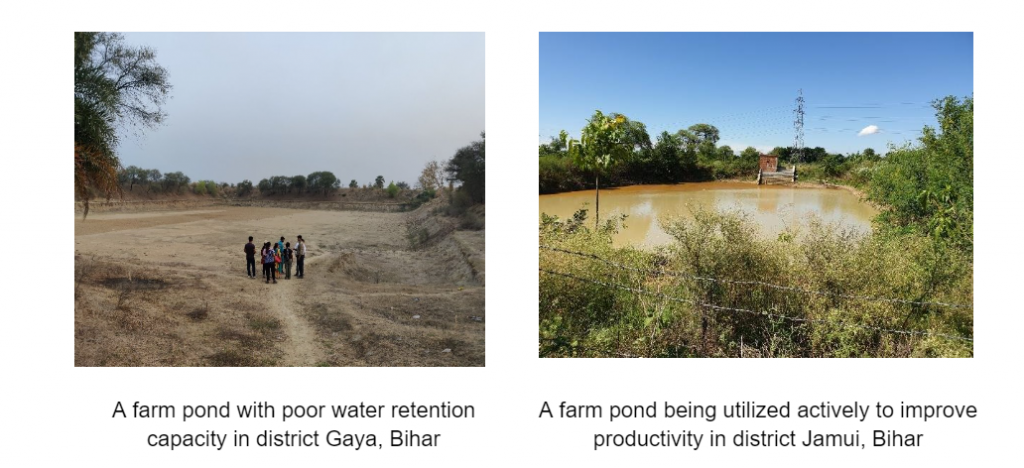

While pursuing this research, our team conducted field visits to locations in three districts , viz. Jamui, Gaya and Koderma, aiming to gather feedback from farmers regarding the effectiveness of farm ponds and resulting outcomes. Our observations revealed a mix of positive instances, where the constructed farm ponds had a beneficial impact on the surrounding farms, and negative instances, such as ponds with inadequate water retention capacity and cases of corruption resulting in the absence of constructed ponds. These observations indicate the importance of assessing the impact of farm ponds constructed under MGNREGA, so that future planning can be more appropriate.

Methodology

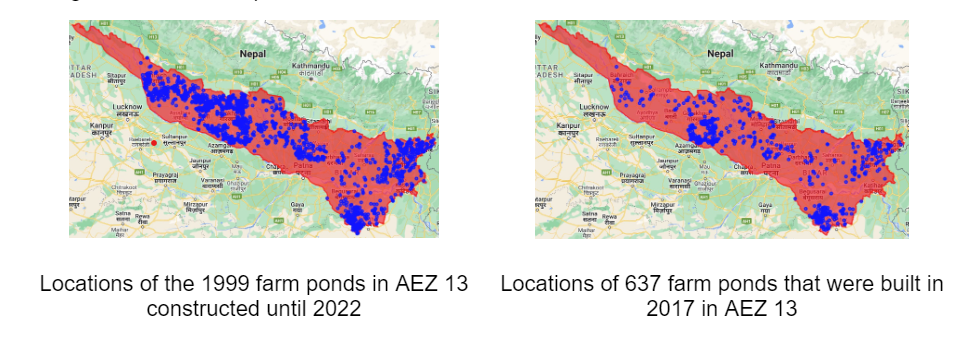

We performed our study on the Agro-ecological Zone 13 (AEZ 13) of India which comprises the northern region of Bihar and the north-western region of Uttar Pradesh. The region is characterized by a hot and wet summer, and a cool and dry winter. Rainfed agriculture is the predominant form of agriculture in the region.

AEZ boundaries of India; AEZ 13 is shaded in red

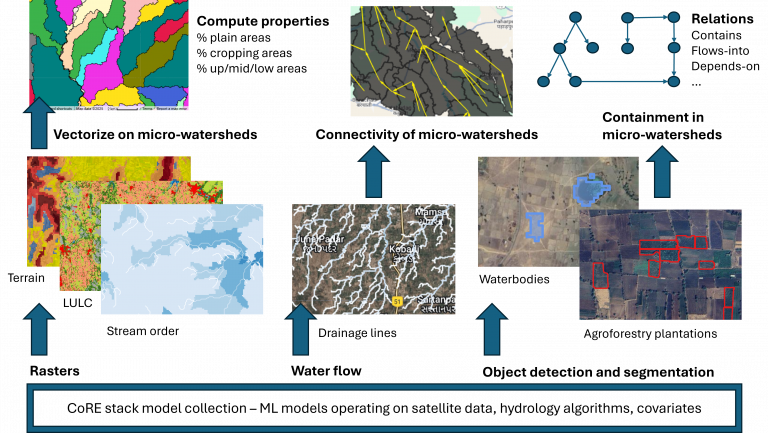

To check the impact of the farm ponds, we selected outcome variables that are known to closely proxy crop yield and crop water stress. The specific indicators that we considered for this purpose are NDVI and GCI (to proxy crop yield), and NDMI (to proxy crop moisture content). We processed satellite imagery from Landsat 7 and Landsat 8 satellite data products to compute these indicators using the Google Earth Engine platform.

To isolate the impact of farm ponds on these outcome indicators, we designed a causal analysis framework, where the treatment or intervention corresponds to the creation of the farm ponds. To get data on the farm ponds that were built under the MGNREGA scheme, we crawled data from MGNREGA MIS and Bhuvan. The data showed that across years the maximum number of farm ponds were built in the year 2017. Therefore, we considered 2017 as the intervention year in our study. The year 2016 was considered as the pre-intervention year or base year since data for some of the remote sensing data products used was available from 2016 onwards. The years 2018 through 2022 were considered as the post-construction years or target years.

Upon analyzing the data corresponding to the 2944 farm ponds in AEZ 13 region that were built or serviced in 2017, we found inaccuracies pertaining to entries of duplicate and non-existent farm ponds, and geo-tagging related errors. We therefore performed a manual cleaning exercise using Google Earth Pro that gave us a cleaner dataset comprising 1999 farm ponds in the AEZ 13 region, of which 637 ponds were built in 2017.

During our visits to locations in AEZ 13 and AEZ 9, we interacted with farmers who got farm ponds constructed under the MGNREGA scheme. Through these interactions we learnt that a farm pond typically helps irrigate 2-3 hectares of land. Therefore, in our computations, we compute the outcomes and covariates in a 100 meters radius buffer around the treated and counterfactual sites. In other words, we assess the impact of farm ponds in a 100 meters radius around the farm ponds.

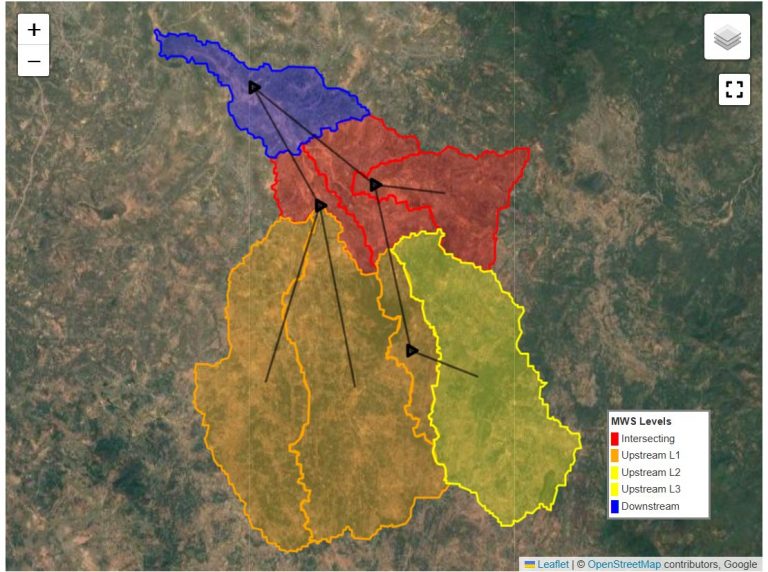

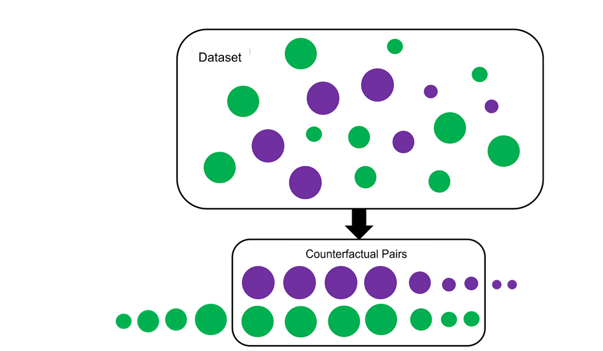

To quantify the impact, we employed the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) methodology. The DiD method compares the difference in outcome at the treated sites to the difference in outcome at counterfactual sites. Counterfactual sites refer to locations that did not receive treatment but share similar characteristics with the treated sites. The characteristic features that are considered for this purpose are known the confounding features or covariates. These are variables that influence both the treatment and outcome.

Illustration of propensity score based matching of treated and counterfactual sites

We selected these covariates based on our prior knowledge of the domain and also upon consulting several implementation organizations to understand the factors they take into consideration when planning farm ponds. The selected covariates can broadly be grouped into three categories, viz., terrain, soil and climate variables, such as the elevation, drainage density, soil properties, precipitation and drought incidence at the site. We used the propensity score matching based method to match the treated sites with counterfactual sites.

Results and conclusions

Our results for the research question on the impact of farm ponds on productivity showed a positive and significant (at p < 0.01) treatment effect of farm ponds for indicators NDVI and GCI in the Kharif (monsoon) season. This indicates that farm ponds do facilitate improvement in productivity during the monsoon season. The treatment effect during the Rabi (winter) and Zaid (summer) seasons was observed to be negative, which indicates that the control or counterfactual locations show better improvement in productivity between the base and target years as compared to that of the treated locations.

We believe that the negative effects during Rabi and Zaid are likely due to unobserved covariates about farm access to other irrigation sources, meaning that the control points identified by us are likely to consist of a mix of croplands with no irrigation sources and those using borewell irrigation. Farms with borewell access will particularly have an advantage during the non-monsoon seasons of Rabi and Zaid, and will show a higher productivity than rain-fed intervention areas which might be leveraging farm ponds. These observations are also indicative of valid site selection of farm ponds, meaning that the ponds are indeed being constructed at sites with lack of alternative sources of irrigation.

Similar to the results for the previous research question, our results for the research question on the impact of farm ponds on productivity during drought years showed a positive and significant treatment effect of farm ponds for indicators NDVI and GCI in the Kharif (monsoon) season. The effects during Rabi and Zaid were observed to be negative or insignificant, which may be attributed to access to borewell irrigation at some of the control locations.

For the research question on impact of farm ponds on sensitivity to droughts, wechecked the variation in impact on varying the number of drought weeks incident or the frequency threshold. For indicators NDVI and GCI, we observed a positive and significant impact until three weeks of drought incidence, which shows that until this limit, farm ponds do help in reducing sensitivity to droughts as compared to the control locations. Beyond three weeks, our results indicate the need for supplemental irrigation to support the crops.

However, for the indicator of NDMI, we observed a consistently positive impact for many weeks, which shows that even during drought conditions farm ponds do help in maintaining the moisture content of the crops as compared to sites without farm ponds.

Our results across the three research questions give conclusive evidence of farm ponds being instrumental in improving productivity during the monsoon season. Our results are consistent with the findings from our field visits where we interacted with farmers owning MGNREGA farm ponds. This feedback provided by farmers played a crucial role in validating and strengthening our research findings, emphasizing the significance of engaging with local stakeholders to ensure the accuracy and relevance of our results.

We are currently working on extending this study to other AEZs in India, through which we aim to capture the variation in treatment effects based on characterisation of farm ponds.

More details of this study can be seen in our paper:

Assessing the impact of farm ponds on agricultural productivity in Northern India – R. Kaur, K. Bansal, D. Garg, R. Sardana, S. Vishnubhatla, S. Agrawal, S. Kumari, P. Singla, and A. Seth.

ACM COMPASS, 2024.