Published on the WEF forum agenda.

- While digital technologies aim to enhance the efficiency of social protection systems for marginalized groups, their implementation often leads to exclusions and a disconnect between citizens and local governance.

- To address challenges, especially given the need for social protection for climate resilience of the poor, there is a pressing need for community-based digital solutions that empower citizens.

- Effective social protection requires robust informational infrastructure that informs citizens about their rights, available support and how to hold local authorities accountable.

Digital technologies have been adopted globally to improve efficiency in various forms of social protection for marginalized individuals and households.

For instance, the digitization of transactions through Management Information Systems (MIS) aims to improve accounting and transparency and strictly enforce administrative procedures. Social registries created through different enumeration methods aim to better target benefits to reach those meeting predefined criteria.

Biometric-based authentication seeks to reduce leakages in welfare distribution, while digital public infrastructure modularizes components (e.g. authentication, bank transfers) to standardize and avoid duplication.

While such efforts claim to save public funds, widespread exclusions have been documented due to poor implementation. Problems include technology failures, biometric mismatches, connectivity issues or data entry errors and fraud stemming from digital literacy gaps between citizens and agents.

Additionally, errors in complex digital pipelines stretching across many agencies are difficult to diagnose and fix, leading to service disruptions.

Years of advocacy by civil society have led to the adoption of offline service centres and last-mile infrastructure to support the digital delivery of social protection. However, these interventions are service-oriented rather than community-based, removing the agency that communities previously used to claim rights.

Appeals against benefit denials, once handled locally, now depend on a distant computer operator, unaccountable to the public. Concerns that could be resolved through local debates must await parliamentary review.

Thus, digitalization seems to have shifted the nature of citizen-state engagement from local to remote, from public forums to electronic screens and has widened the gap between citizens and the state, weakening grassroots democracy.

Yet, in today’s world, with intersecting challenges of the environment, livelihoods and social justice, what is most needed is the opposite: stronger, collectivized communities with a shared understanding of these crises to align on coordinated local action. This is increasingly important given the crucial need for social protection for the poor who are likely to face the impact of climate change the hardest.

Leveraging technology

So, what digital tools and technologies can equip social protection so communities can build resilience and prosperity?

Following are examples that speak to social protection schemes geared towards climate resilience and income support, noting the information infrastructure necessary to reach their goals effectively.

1. Traditional knowledge and digital tools

Despite the existence of social protection schemes for climate resilience, the sustainability and integrity of many ecological systems stands in jeopardy because of fault-lines of a disconnect between short-term and long-term priorities and between individual and common good.

For one, the slow movement away from chemical fertilizers that lead to soil degradation, the increasing use of groundwater for irrigation – that results in depleted aquifers and water stress – and the degradation of forest ecosystems – due to logging and unrestricted harvesting of forest produce – are driven by the imperatives of individual economic mobility and short-term gain at the cost of broader common good.

A good starting point for communities to come together and create action plans for using social protection resources is to build a shared understanding of the challenges they face in their local environment, how these challenges developed and how to incorporate their traditional knowledge of how to care for the land.

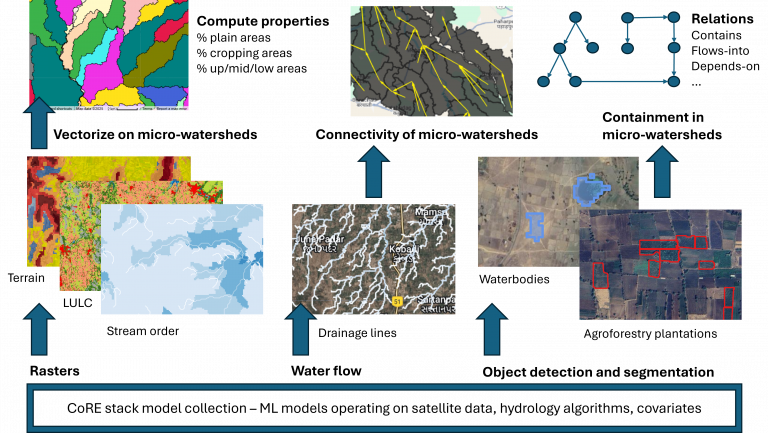

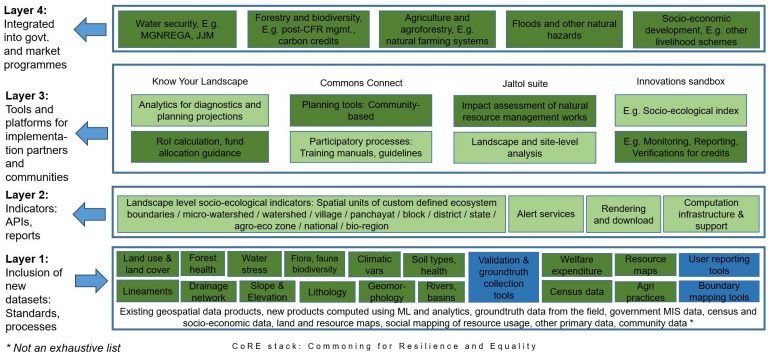

Digital technologies like data platforms and environmental monitoring tools can provide communities with better access to insights that need to be deliberated.

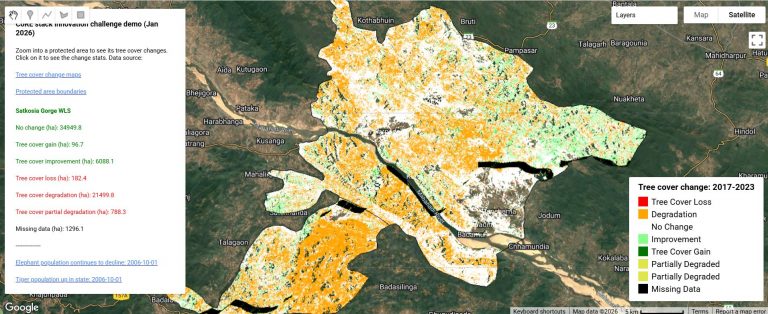

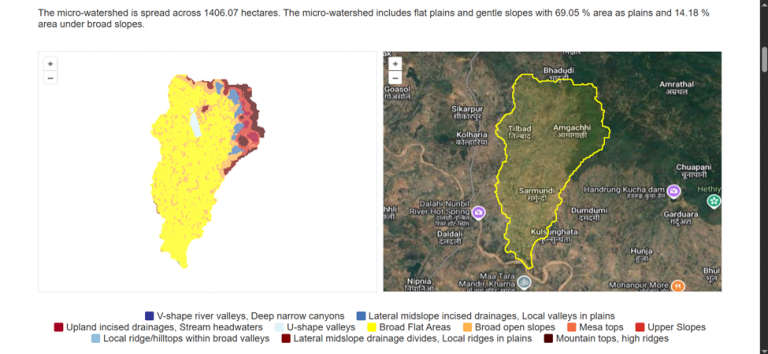

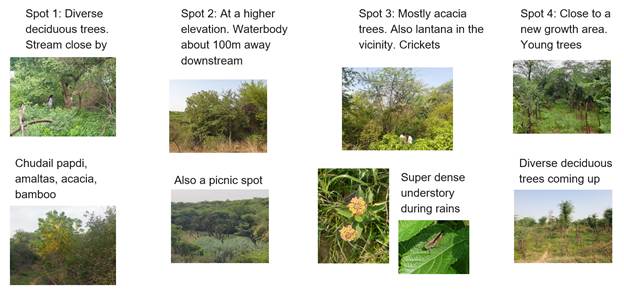

For example, platforms such as the CoRE stack can enable communities to use a variety of sensors to monitor their local ecosystems closely, providing detailed insights and real-time data that can support informed decision-making and strengthen their ability to manage local resources.

2. Enhancing access and representation in social protection

Many income-enhancing social protection schemes should proportionally benefit marginalized groups but inequalities persist and perpetuate despite these measures. This is because marginalized groups and households are often underrepresented or overlooked across multiple levels – social, political and economic – making it difficult for them to influence policies, access resources or participate fully in the processes that affect their lives.

Historical oppression compounds this and therefore, they may not have the resources to follow-up on past demands which may simply get lost due to administrative inaction, or even worse, discrimination.

What kind of digitalization can help here? Many countries, including India do have a rich architecture of governance decentralization that is specifically meant to be demand-driven to bring procedural equity but the day-to-day workings of local governance are often not transparent and make it harder to illuminate any procedural gaps.

Digitalization alone is, of course, insufficient to address this but can serve as a first step to bring transparency and put information in the hands of marginalized communities to demand accountability. It will have to be augmented with a social infrastructure that can leverage this information and history tells us that such mobilization does come about and can improve distributive justice when the right information is made available to citizens.

3. Digital infrastructure in advocacy

To make these schemes more effective, it’s important to have a system that helps people understand their rights, how to access support and how to hold local authorities accountable.

Many citizens don’t know what opportunities exist to strengthen their communities against climate challenges or how to make the best use of any financial support they receive. Clear information and guidance can help them make better decisions and advocate for their needs.

For example, moving from cropping to plantations of fruit trees in drought-prone areas can be helpful. However, these plantations would prosper for communities if they knew about the social protection schemes and had access to advisories to manage the plantations – trimming the canopy, watching for infestations etc.

Access to cash flow and zero delay between activities – planting saplings, putting up fencing, access to fertilizer, access to water, etc. – is also critical, requiring the system to work like clockwork. A digital informational infrastructure to provide inputs, raise grievances, and track progress transparently can support social protection schemes in operating more effectively.

Voice-based platforms such as Mobile Vaani have enabled rural communities to access such know-how, learn from one another, and use media to strengthen social accountability. Simple SMS alerts informing communities of how much and when resources were distributed in their villages have led to greater citizen satisfaction.

Building community power with digital tools

Digital technologies for social protection can lead to more democratic outcomes if designed to empower communities to advocate for their needs rather than only to make service delivery more efficient for agencies.

What’s needed today is a community-focused approach that helps people build a shared understanding of local challenges, work together towards common goals, promote equality and strengthen accountability at the local level. Creating digital tools centred around communities would result in a very different, more empowering system than we see today.